| |

"Implementation of wireless biomedical sensors in advanced

clinical care"

Authors: Karl Oyri¹, Ilangko Balasingham¹,

Jan-Olav Høgetveit²

Speaker: Karl Oyri

Origin Institution:

¹ The Interventional Centre, Rikshospitalet University Hospital

² Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rikshospitalet University

Hospital

E-mail: karl.oyri@klinmed.uio.no

County: Norway

Post Address:

Karl Oyri

The Interventional Centre

Rikshospitalet University Hospital

0027 Oslo

Norway

Thematic: wireless technology, point of care data, invasive

blood pressure, biomedical sensor

Índice

general

Introduction

The Wireless Health and Care Project (WSHC) (1),

partly funded by the Norwegian Research Council, focuses on wireless

technology in healthcare. WSHC involves industrial-, research Institute-,

and clinical partners. The Interventional Centre (IVC) at Rikshospitalet

University Hospital in Oslo, Norway is one of the clinical partners.

As part of the WSHC Project, research was performed at IVC to evaluate

the use of wireless biomedical sensors in clinical practice. The

research hypothesis was that a difference between wired and wireless

pressure measurements was to be expected.

Methods

Sensor data from a modular wireless non-disposable piezoresistive

biomedical sensor prototype for continuous invasive blood pressure

measurement and continuous 2-channel ECG developed by MemsCap (2)

was compared with a state of the art patient monitoring system from

Siemens Medical utilizing disposable biomedical sensors from Edwards

Lifesciences (3). Measurements were performed in

a clinical trial involving four major laparoscopic surgical procedures.

The wireless standard Bluetooth (4) was used, as

investigated in an OR setting (5). High resolution

data from the two types of biomedical sensors were collected in

customized LabView applications (6) during the

surgical procedures and compared in MatLab (6)

statistically and sample-by-sample for visual inspection at a sampling

rate of 100HZ.

Results

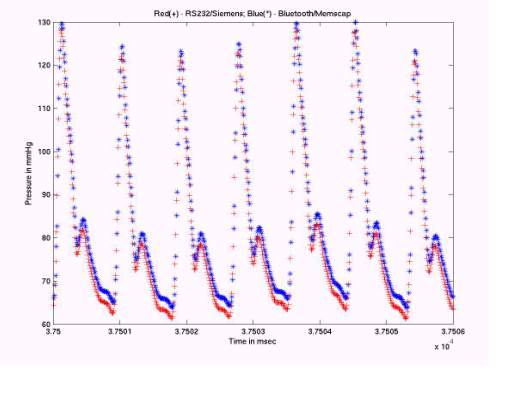

We observed a very high rate of correlation between signal amplitudes

of the wireless and wired biomedical sensors during four laparoscopic

surgical procedures. This correlation is illustrated in Figure 1.

Discussion

Small changes in technology for invasive blood pressure measurement

have taken place last three decades (7). Transportation

of critically ill patients require adequate planning and monitoring

during transport (8 -10). Uninterrupted

wireless monitoring facilitates intrahospital patient transport.

Wireless monitoring replaces cables and reduce the potential risk

for adverse events related to disconnection (10).

Wireless technology also is battery driven, thus suitable for pre-hospital

patient monitoring. Traditional patient monitors are expensive and

operate on proprietary platforms, producing analog signals. Processing

of digital signals is of great interest in the point of care clinical

setting (11). The wireless biomedical sensor prototype

represents a low-cost, reliable and flexible alternative to traditional

signal transmission and data processing.

Conclusion

Wireless transmission of blood pressure data and EKG signals in

the OR is a stable, accurate and simple method with a potential

for developing new and cost-effective procedures, and to replace

traditional monitoring solutions based on cables.

Bibliography

(1)

Wireless Health and Care. http://www wshc no/ 2004 [cited 2004 Oct

30];Available from: URL: http://www.wshc.no/

(2) Wireless Physiological Pressure Transducer.

2004. Ref Type: Pamphlet

(3) Truwave PX 600F Pressure Monitoring Set. 2004.

Edwards Lifesciences Germany GmbH. Ref Type: Pamphlet

(4) Bluetooth. https://www bluetooth org/ 2004 [cited

2004 Oct 30];Available from: URL: https://www.bluetooth.org/

(5) Wallin MK, Wajntraub S. Evaluation of Bluetooth

as a replacement for cables in intensive care and surgery. Anesthesia

& Analgesia 2004 Mar;98(3):763-7.

(6) National Instruments. http://www ni com/ 2004

[cited 2004 Nov 8];Available from: URL: http://www.ni.com/

(7) Craft RL. Trends in technology and the future

intensive care unit. [Review] [65 refs]. Critical Care Medicine

29(8 Suppl):N151-8, 2001 Aug;29.

(8) Szem JW, Hydo LJ, Fischer E, Kapur S, Klemperer

J, Barie PS. High-risk intrahospital transport of critically ill

patients: safety and outcome of the necessary "road trip".

Critical Care Medicine 1995 Oct;23(10):1660-6.

(9) Velmahos GC, Demetriades D, Ghilardi M, Rhee

P, Petrone P, Chan LS. Life support for trauma and transport: a

mobile ICU for safe in-hospital transport of critically injured

patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2004;199(1):62-8.

(10) Smith I, Fleming S, Cernaianu A. Mishaps during

transport from the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine 1990

Mar;18(3):278-81.

(11) Celi LA, Hassan E, Marquardt C, Breslow M,

Rosenfeld B. The eICU: it's not just telemedicine. Critical Care

Medicine 2001 Aug;29(8 Suppl):183-9.

Figure

1: Wired and wireless blood pressure samples.

|